Will it finally be the ordinary Filipino's turn?

When will it be the turn of the ordinary Filipino? Hardly after this election. The elites have full control and secure their own interests.

(this is the first of three reports from the Philippines, which I visited from April 4 to 25, 2025)

On May 12, Filipinos go to the polls. All 317 seats in the House of Representatives and 12 out of 24 seats in the Senate are up for election. The elected representatives will make up the 20th Philippine Congress. In addition, local elections will be held in all provinces, cities and municipalities. At the same time, the election marks the halfway point in the six-year presidential term of Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr.

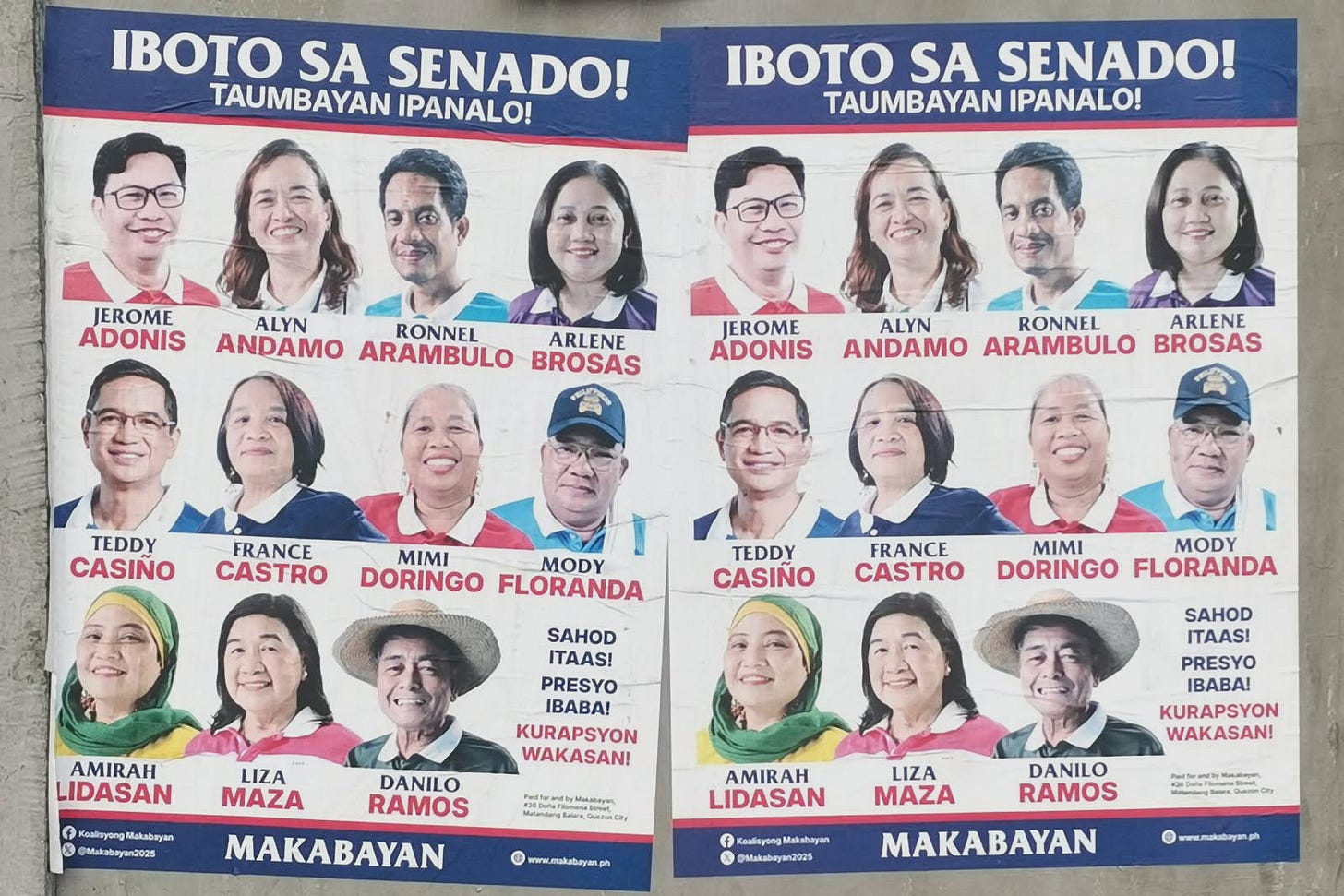

The election campaign is in full swing when I land in early April. Election posters are hanging in every street, and political advertisements are running on TV channels. Philippine politics is not immediately understandable from a Norwegian context. It's not obvious what policies the parties, lists or candidates stand for. There are a number of parties, and the landscape is changeable. The political parties form political coalitions ahead of the congressional elections. In this election, four coalitions have been formed, each containing several parties.

The impression is otherwise that alliances are formed and dissolved. Everything can be sold for positions, and candidates seem to choose a party according to what serves the individual at the moment. The election posters don't necessarily make you any wiser. There is a strong focus on personality, pictures of the candidate with name and candidate number seem to be enough, while slogans or main political issues are often completely absent.

In the period leading up to national mid-term elections on 12.05.2025, travelers are encouraged to exercise particular caution and listen to the advice of local authorities, as the risk of violence may increase and the threat situation in general may worsen.

- Philippines, travel information (Regjeringen.no – the Norwegian government)

The fight against poverty, crime and corruption are classic election campaign issues that all candidates believe they can combat. When the political program is strikingly similar, it is the candidates' personal integrity that is promoted as a winning issue.

Marcos vs. Duterte

Philippine politics has a strong element of political dynasties, where families hold political positions for generations. Being the son or daughter of a politician seems to be a qualification in itself. The current president is the best or worst example in this respect. This year, the Marcos clan can celebrate 100 years since the first Marcos was elected to Congress.

President “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. has registered a sharp decline in support and confidence. His popularity fell by as much as 17% last month, from 42% in February to 25% in March. 53% of voters say they are openly dissatisfied with the president. Voters disapprove of his efforts to control inflation (79%), fight theft and corruption (53%), reduce poverty (48%) and increase workers' wages (48%).

At the same time, Vice President Sara Duterte's popularity is growing. 59% of voters are satisfied with the job she is doing, up 7% from the previous month. She is thus emerging as a favorite for the presidential election in 2028.

The investigation was conducted just days after the Vice President's father, former President Rodrigo Duterte, was arrested and handed over to the International Criminal Court. The Philippines is the second country in history to have arrested a former head of state or government and assisted in their transfer to the ICC (the first was Côte d'Ivoire in the case against Laurent Gbagbo).

President “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. made a U-turn. He had previously promised not to cooperate with the ICC, but eventually approved the arrest of Duterte on the grounds that he was committed to Interpol. The ICC may also have used the political rivalry between the Marcos and Duterte families to go after the ex-president.

Regardless of the crimes Rodrigo Duterte is accused of, it is a fact that he is still very popular among broad sections of the population. This may also help to explain President Marcos Jr.'s sharp drop in the polls.

Pacquiao is ready for a new round in the political ring

Celebrity status, created in the entertainment industry or in the sports arena, can be translated into political capital. One example is boxer Manny Pacquiao, long considered the best in the world, regardless of weight class. He was the first person in history to win the world title in four of the eight original weight classes in boxing, and the only person to win world championships in four decades (1990s, 2000s, 2010s and 2020s).

Of course, these achievements made him a folk hero, and his popularity carried him straight into the House of Representatives in 2010, where he served two terms before being elected senator in 2016. In 2021, he declared himself a presidential candidate as well, coming third in the 2022 presidential election with 4 million votes, an election “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. clearly won.

Pacquiao was an active boxer until 2021. He was criticized for being the most absent congressman in the 2013-2016 term, which was repeated in the following term when, as a senator, he had the worst attendance among all senators in the 17th Congress. But on May 12, he will once again be at the service of the people, and for a second term in the Senate. Pacquiao has recently announced his switch to the President's party.

The elites are in full control

In 2022, “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. ran as a presidential candidate for the Partido Federal ng Pilipinas (PFP) and won with almost 59% of the vote. The party was founded as recently as 2018. Marcos Jr.'s party is part of a coalition with five other parties, which can be briefly described as nationalist and conservative. These include the Nacionalista Party (NP), which was the central party throughout much of the 20th century. The coalition is called Alyansa para sa Bagong Pilipinas, and currently holds 187 seats in the House of Representatives and has the support of 11 of 24 senators.

DuterTen (or Duter10) is the name of the opposition coalition, which supports the Duterte camp. The central party is Hugpong ng Pagbabago (HNP), formed in 2018 by Sara Duterte to support her father Rodrigo Duterte's administration. Three other parties are part of the coalition, which currently has only 6 seats in the House of Representatives and 3 senators. Sara Duterte's growing popularity could give DuterTen a stronger mandate after the election.

KiBam is the name of the third coalition, in which the liberal Partido Liberalng Pilipinas (LP) is central. The party was founded as early as 1946, as a breakaway from the Nacionalista Party. The party was an opposition party against the dictatorship of its former member Ferdinand Marcos, and re-emerged as an important political party after the People Power revolution in 1986. The social democratic Akbayan is also part of KiBam, along with a small regional party from Cavite. The coalition currently has 11 seats in the House of Representatives and one senator.

Where is the left?

Who should Filipinos who want social change vote for? Of the four coalitions, Makabayan stands out as the alternative. In this election, four parties are running candidates for the coalition: Alliance of Concerned Teachers (ACT-Teachers), Gabriela Women's Party, Kabataan Partylist (KPL) and Bayan Muna.

However, Makabayan is weak, and in the current term the coalition has only 3 elected in the House of Representatives and none in the Senate.

And what about the communists? The Philippine Communist Party (PKP 1930) is today a completely insignificant entity without any representation. The party experienced a split in 1968. A growing wing of the originally Soviet-oriented Communist Party looked to China and Maoism and, under the leadership of Jose Maria Sison, founded the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) in 1969. The armed wing, the New Peoples Army, has all these years waged guerrilla warfare against the government, where they have been particularly active in the countryside.

Peace talks were initiated in 1986. Norway facilitated the negotiations from 2001, with talks in Oslo and other cities in Europe, where the communists were represented by the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP). The then newly elected Rodrigo Duterte put peace negotiations high on the agenda, and in August 2016 they resumed in Oslo after a five-year standstill. Optimism was high. In February 2017, however, things came to an abrupt halt when the New People's Army killed several government soldiers in an ambush. The Philippines government declared the group a terrorist organization in 2021.

Left-wing activists live dangerously

Being a social radical, trade union activist, indigenous rights advocate or environmentalist, socialist, not to mention communist, can come with a high price in the Philippines. The phenomenon of red-tagging, which involves accusing individuals and organizations of being communists or communist sympathizers, is a serious problem. Political assassinations are common, and often police officers or outright assassins are behind them. Rarely is anyone convicted of such liquidations.

In its report from 2024, Human Rights Watch writes:

"Red-tagging, which frequently occurs online and in the media, often leads to physical violence. In recent years, targets have expanded from left-wing activists to indigenous leaders, land rights defenders and teachers. Union leaders have also been harassed by government agents because of union activities."

Free and fair elections?

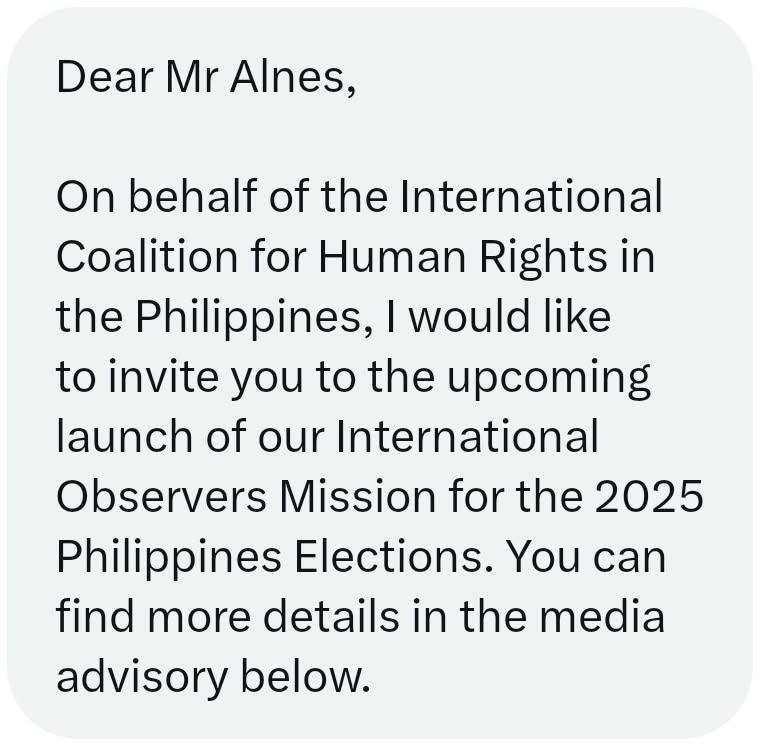

Two days before I traveled home, I received this message from ICHRP:

Ahead of the 2022 presidential election, the ICHRP documented election-related human rights violations, including vote buying, failures in the electronic counting system, misinformation, red-tagging and intimidation, and even killings. The ICHRP concluded in its final report that the presidential election was neither free nor fair.

Following the arrest of former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte by the International Criminal Court and the months-long dispute between the Marcos and Duterte families, ICHRP is sending a new delegation to provide independent observation of these elections.

“Amid ongoing reports of election fraud, disinformation, and violence related to the electoral process—all against the backdrop of a constantly worsening human rights situation in the Philippines, marked by frequent disappearances, bombings of civilian communities in the countryside, and de facto martial law—it is more urgent than ever that independent observers collect, analyze, and project their findings to the international community”, ICHRP says.